In the past, a country’s leader came under scrutiny if they acted against the interests of their own nation, if they became a traitor. Today, those who refuse to abandon their national interests and do not blindly support international capital are publicly vilified by the paid media and those representing multicultural, globalist interests. Of course, there have always been conflicting interests between political forces, often driven by ideological differences or personality defects. But reflecting on the current situation, it becomes clear that the common ground among those who are rejected is not similarity. Leaders of vastly different countries, sometimes from divergent cultures or with varying degrees of influence on the world, suddenly find themselves sharing the “bitter bread” of exclusion.

Many leaders could be included in this group, but let’s highlight just two – Putin and Orbán – whose political activities prove the above statement. Objectively speaking, there is almost nothing in common in the opportunities available to these two leaders. Yet they find themselves on the same platform, with their political visions intertwined due to the political tastes of the past and present.

The “school of the past” was based on national affiliation, even during the flourishing of alliance systems. However, belonging to today’s dominant international caste – while not excluding it – does not particularly favor the ideal of thinking in national terms. Anyone who raises the banner with the slogan “Nations Above All” can expect total ostracism.

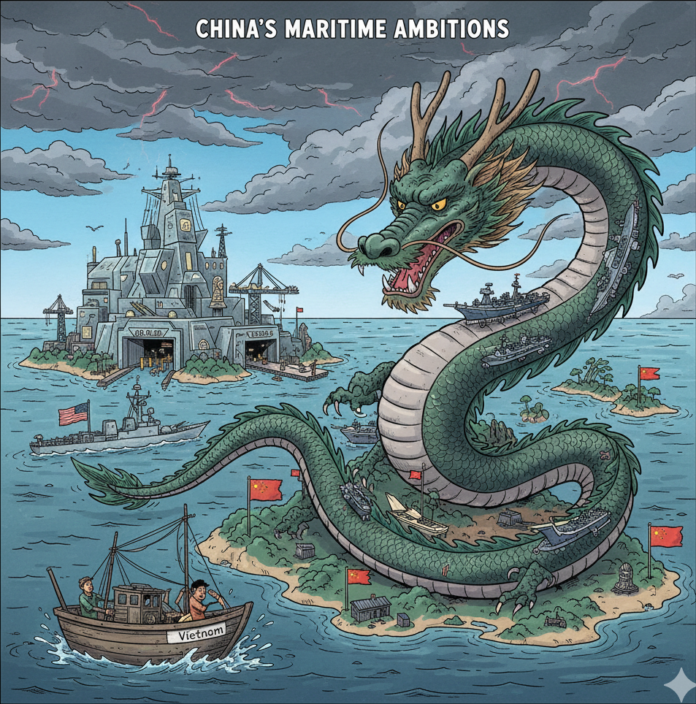

This is why desperate and imaginative negative labels are hurled at Putin. Orbán and others face similar treatment if they maintain relationships – especially business ties – with the Russians. Let’s set aside the fact that the self-proclaimed “developed” countries of the world also maintain business relationships with the “great Russian land.” For example, the USA sources significant materials for its nuclear industry from Putin’s country. In fact, U.S.-Russian trade has shown growth over the past two years. Ignoring all this, let’s focus on why Putin and his system must be hated. In short: because he represents a different policy than the economic powers that dominate and seek to control the world economy, like BlackRock. In a more extended explanation: the so-called “outdated” political style rejects and even dares to rebel against servile subordination.

Today, this kind of national consciousness has strengthened particularly in Central and Eastern Europe. The background is that in the 1990s, the rulers of Wall Street began buying up the assets of countries, still politically dazed by the regime change, at depressed prices. This was the situation during the era of President Yeltsin in Russia. The Yukos oil company and its leader, Khodorkovsky, exemplify the trend of that time. With “internal” help, American funds began purchasing the company’s shares, acquiring ownership rights to vast Siberian oil reserves. The Khodorkovsky-led betrayal had two consequences: Russia was pushed to the brink of collapse, and Yeltsin drowned his helplessness in alcohol.

Then came Putin and his operative team. They took back ownership, chased away the robber capital, and as an example, sent Khodorkovsky to Siberia to study the challenging process of oil and gas extraction up close.

Since then, there has been only one slogan in the dictionary of Putin, supported by the majority of Russian voters: “Russia belongs to the Russians.” Putin translated this slogan from the American version: “America belongs to the Americans.” The new Russian leadership then declared that Russia would remain Christian in the future and would not be misled into accepting mad ideas disguised as culture.

Because – as they said – man and woman were created, and that’s it! Anyone who defines themselves differently is undesirable in the public sphere within the country. The pedophile, being a criminal, will experience the rugged lifestyle of Siberia. The ultimate – and condemned by Western democracy – audacity was that Putin restored Russia’s security guarantees, stabilizing its defense against external threats.

Now, let’s take a leap into recent European history. In Europe 2024, serious figures write and say daily that Viktor Orbán is nothing more than Putin’s lackey, the mocker of democracy and European values. Why do they persist with these accusations? And if they criticize someone, why don’t they do it “on their own merits”? Why do they need to bring in the Russian president or anyone else? Perhaps because the loudmouths and accusers are projecting their own life situations onto the Hungarian Prime Minister. It can’t be easy for them to digest that they receive daily instructions from across the ocean.

There may be some truth in the fact that

the two statesmen, far from the contamination of Brussels, are driven by undeniably similar motivations. The nation’s interest above all! Consistently standing by this principle, it is not surprising that their enemies are the same. Moreover, both reject the mafia’s law,

which, regarding destruction, only admits while pulling the trigger of the gun aimed at the rebellious head: “Nothing personal, it’s just business.” In Western Europe, this principle clearly dominates political circles.

The question here is not about Putin or Orbán. It is much more about what kind of future the citizens of nations envision. Perhaps, one day, it will also become clear that

over there in Russia or here along the Danube, the political leaders are so brave because they believe it is right to be accountable to the members of their own society for the motivations behind their decisions.

After all, the essence of survival is not the gun but consistent value retention.

Laszló Földi